In a world that often clamors with noise and chaos, St. Benedict’s teachings remind us of the value of silence, prayer, and reflection, offering a path to personal transformation and deeper communion with God.

Benedict’s feast day, July 11, is an occasion for the faithful to reflect upon his remarkable life, but Benedictine devotion is a year-round, life-long practice for many Catholics, especially monastics and exorcists. Benedict’s biography is a testament to his enduring influence on religious life in the Christian West.

The Catholic Church is a faith steeped in tradition and history, richly adorned by the narratives of countless men and women who, in their lives, strived to live out Christ’s teachings. These saints are spiritual giants, their stories offering inspiration and guidance for followers of the faith.

One such towering figure is Saint Benedict of Nursia, the father of Western monasticism.

From Riches To Rags

This article is a sample of our new book St. Benedict: Monk, Mystic, Exorcist

Born with his twin sister in the small Italian town of Nursia around 480 AD, Benedict came of age during a time of significant upheaval. The Western Roman Empire had recently collapsed, giving rise to an era of political and social chaos.

Amid this tumult, Benedict’s affluent parents managed to send him to Rome for studies. However, disappointed by the city’s moral decadence, he withdrew from worldly life and retreated to the solitude of a cave in Subiaco.

For three years, Benedict led a life of seclusion and prayer in Subiaco. His holy reputation gradually attracted many followers, prompting him to establish a dozen small monasteries in the vicinity. Unfortunately, Benedict faced opposition, envy, and even attempts on his life. He eventually decided to leave Subiaco, along with a group of disciples, and journeyed to Monte Cassino.

At Monte Cassino, situated halfway between Rome and Naples, St. Benedict built his crowning achievement: a large monastery intended to be a beacon of Christian life. Here, he wrote the ‘Rule of St. Benedict,’ a set of precepts for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot. The Rule, encapsulated in the maxim “Ora et Labora” (Pray and Work), provided a balance between spiritual and manual work, emphasizing humility, obedience, and above all, the love of Christ and neighbor.

Benedict was also known for his extraordinary spiritual gifts. His gift of prophecy was attested to in numerous accounts, from foreseeing the destruction of his own monastery in Monte Cassino to predicting the day of his death.

Benedict was also known for his extraordinary spiritual gifts. His gift of prophecy was attested to in numerous accounts, from foreseeing the destruction of his own monastery in Monte Cassino to predicting the day of his death.

His profound visions, another one of his spiritual gifts, were not only a source of personal revelation but also provided guidance and wisdom to his followers. They were at times practical, revealing the presence of hidden food during times of scarcity, and at times they were deeply mystical, like his renowned vision of the world in a single ray of sunlight, symbolizing the interconnectedness of all creation.

Healing, too, was a part of his miraculous gifts. He was said to have healed numerous people, from monks in his own community to the Roman patrician, Servandus. And, on multiple occasions, he reportedly drove out evil spirits, enhancing his reputation as a spiritual warrior against evil forces. His ability to survive attempts on his life through divine intervention, including being poisoned twice, further testify to the supernatural protection that enveloped him.

St. Benedict passed away on March 21, 547 AD, having accurately foreseen and predicted the circumstances and exact date, but his legacy lived on in an extraordinary way. The ‘Rule of St. Benedict’ became the foundational text for monastic life in the West. Monasteries following his Rule proliferated across Europe, preserving literacy and learning during the Middle Ages when much of the continent was plunged into darkness.

St. Benedict and the Poison Cup

St. Benedict’s survival of attempted poisoning is one of the most well-known stories about his life, and it comes from St. Gregory the Great’s Dialogues, a primary source of information about St. Benedict.

While St. Benedict was living at Vicovaro, in the community he had joined after leaving his life of solitude in Subiaco, his strict adherence to the monastic rules and his ascetic way of life did not sit well with the other monks. The austerity and discipline he advocated as the prior of the community were viewed as excessively harsh by the monks who had a more relaxed interpretation of monastic living.

Feeling threatened by the changes he was instigating, the monks decided to poison him to rid themselves of his leadership. They laced his drink with poison and served it to him.

However, as was his custom, St. Benedict performed the sign of the cross over the cup before he drank from it. As he made the sign of the cross, the cup that held the poisoned drink shattered, spilling its contents. This miraculous event is interpreted as divine intervention to save St. Benedict’s life.

Realizing that the community did not share his commitment to strict monastic observance, St. Benedict chose to leave Vicovaro. The experience at Vicovaro may have influenced his later approach to monastic life, leading him to establish his own monasteries where the rigors of monastic discipline could be fully observed.

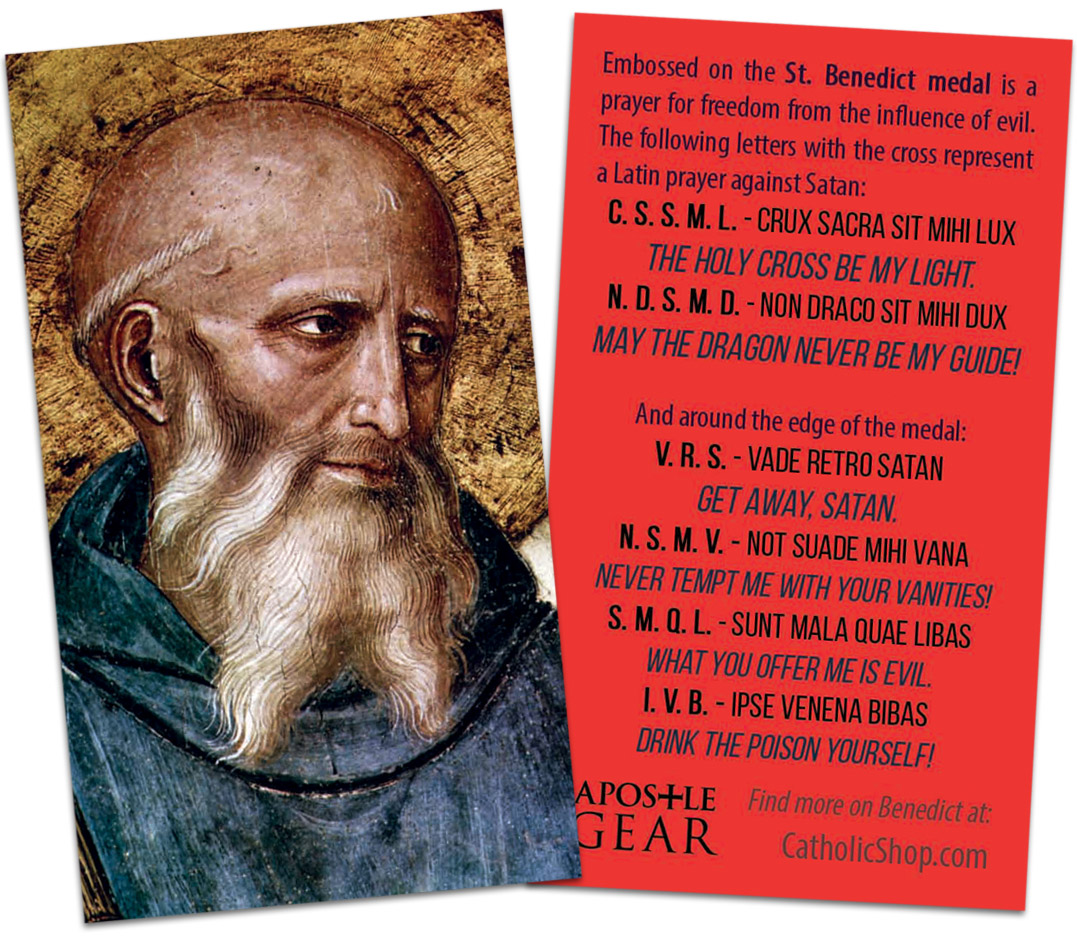

The event is often depicted in artwork related to St. Benedict, emphasizing the miraculous protection granted to him. It is also commemorated in the design of the St. Benedict Medal, which includes the image of the cup and a raven, which is associated with another poisoning attempt that St. Benedict survived.

St. Benedict and the Poison Bread

The second attempt on St. Benedict’s life through poisoning is another memorable incident from his life. This event, like the first, is recorded in St. Gregory the Great’s “Dialogues”.

After leaving Vicovaro, St. Benedict returned to Subiaco and established a series of monasteries. His reputation for holiness and wisdom attracted many, but it also aroused the envy and malice of a local priest named Florentius.

Florentius became envious of Benedict due to the growing reputation of the young monastic leader. As Benedict attracted more and more followers, Florentius perceived him as a threat to his own prestige and influence. This envy fueled a bitter conflict, which involved several attempts by Florentius to harm or discredit Benedict.

In the first instance, Florentius tried to tarnish Benedict’s reputation by sending seven promiscuous women into the monastery to distract the monks and lead them into sin. However, upon seeing them, Benedict immediately realized the danger and fled the monastery with a few monks, going to live in the mountains near Subiaco.

In the first instance, Florentius tried to tarnish Benedict’s reputation by sending seven promiscuous women into the monastery to distract the monks and lead them into sin. However, upon seeing them, Benedict immediately realized the danger and fled the monastery with a few monks, going to live in the mountains near Subiaco.

Unable to bear St. Benedict’s growing influence, Florentius resolved to kill him. He sent to St. Benedict a loaf of bread laced with poison. But Benedict, who had the gift of discernment, seemed to know that the bread was poisoned; he commanded a raven, which had been coming to him daily for a piece of bread, to take the poisoned loaf and dispose of it where no one could find it. The raven complied, and when it returned, Benedict gave the bird his blessing.

The story of the raven and the poisoned bread is often depicted in art about St. Benedict, emphasizing the saint’s deep connection with creation and his divine protection. The incident is also symbolized on the St. Benedict Medal, with the raven and the poisoned loaf depicted alongside the shattered cup from the first poisoning attempt.

Lastly, in his blind envy and rage, Florentius plotted to destroy the monastic buildings at Subiaco by collapsing them. However, before the plan could be carried out, the building in which Florentius himself was standing collapsed, killing him instantly. Benedict, upon hearing the news, was deeply sorrowful for the tragic end of Florentius.

The conflict with Florentius is significant as it highlights the opposition St. Benedict faced due to his growing influence and the establishment of his monastic communities. Moreover, the way Benedict handled these situations – with patience, wisdom, and compassion – offers insight into his character and holiness.

The two instances of attempted poisoning, and St. Benedict’s miraculous survival, greatly contributed to his reputation as a holy man protected by God. It also highlights the fact that Benedict’s life was fraught with tribulation and persecution, and the conflict between St. Benedict and Florentius is perhaps one of the ways in which Benedict became associated with protection from evil.

Thankfully, Benedict’s leadership and the communal strength of the monastic brotherhood resisted these destructive effort. But the repeated attacks and escalating envy from opponents compelled Benedict to leave Subiaco. Accompanied by a group of his loyal monks, he moved south to establish the famous monastery of Monte Cassino, marking the end of his time in Subiaco.

Despite the opposition he faced, the years in Subiaco were critical for St. Benedict. They shaped his spiritual vision, which would later be codified in his Rule, providing a foundation for the monastic tradition that continues to thrive in the Catholic Church today.

Resurrection of a Young Monk

The Resurrection of a Young Monk is an amazing story of St. Benedict’s miraculous power that has been passed down through centuries. This tale was narrated by Pope St. Gregory the Great in his Dialogues, a series of writings on the lives of early saints.

The story begins when a young noblman, named Placidus, was entrusted to St. Benedict at Subiaco for his spiritual education. He quickly advanced in virtue and holiness under the tutelage of the great abbot.

One day, a monk who was assigned to garden duties accidentally sliced off his own foot with a hoe while working. Hearing the cries of the monk, others quickly came to his aid, bringing the severed foot to St. Benedict.

St. Benedict took the severed foot and the suffering monk into the oratory. He ordered the others to leave them, and he shut the door. With the injured man and the detached foot lying before him, St. Benedict began to pray. He prayed fervently, calling upon the healing power of Christ.

As St. Benedict prayed, the miraculous happened – the foot was reattached, and there was no trace of the severe injury. The monk was astounded and overwhelmed with joy. He got up, put on his sandals, and returned to his gardening work, perfectly healed.

This miraculous story of St. Benedict resurrecting the severed foot of the young monk not only testifies to the extraordinary divine powers he was granted but also stands as a testament to his deep faith, prayerful intercession, and compassionate love for his spiritual children. The story underlines the fact that nothing is impossible for God, and that faith and prayer can lead to extraordinary miracles.

The Miracle of the Broken Sieve

The Miracle of the Broken Sieve is one of the earliest tales of St. Benedict’s life, as recounted by St. Gregory the Great in his Dialogues. This event occurred during Benedict’s youth while he was still in the village of Enfide (Effide), near Subiaco, before he embarked on his monastic journey.

The story goes that, one day, a servant borrowed a sieve – a utensil used for sifting grain – from a neighboring house. In the course of his duties, the servant accidentally dropped the sieve, causing it to shatter into pieces. Fearful of the repercussions, the servant was overcome with distress.

Seeing the servant’s despair, young Benedict, who was not yet fully aware of the divine grace he had been granted, was moved by compassion. He took the broken pieces of the sieve, went to a private place, and began to pray fervently. As he prayed, the sieve miraculously mended itself, with the pieces joining together, leaving no trace of the previous damage.

Seeing the servant’s despair, young Benedict, who was not yet fully aware of the divine grace he had been granted, was moved by compassion. He took the broken pieces of the sieve, went to a private place, and began to pray fervently. As he prayed, the sieve miraculously mended itself, with the pieces joining together, leaving no trace of the previous damage.

Benedict returned the perfectly restored sieve to the stunned servant, thereby relieving him of his distress. The miraculous event, however, began to draw attention and aroused talk among the local villagers. Fearful of the growing attention and seeking to avoid pride, Benedict soon left Enfide, retreating to the solitude of a cave in Subiaco. There, he would grow into the holy man known to us as St. Benedict, the founder of Western monasticism.

The sieve is said to have been kept at the monastery of Subiaco as a relic, a testimony to this early miracle in the life of St. Benedict. Through this story, we are reminded of St. Benedict’s compassion, humility, and the divine grace that worked through him, even before his formal commitment to religious life.

The Miracle of the Loaf and the Glass

The Miracle of the Loaf and the Glass is another noteworthy incident in the life of St. Benedict that displays his divine foresight and miraculous capabilities. As with other episodes from his life, it is captured eloquently in St. Gregory the Great’s Dialogues.

The story goes that a certain man sent his servant to St. Benedict with a flask of wine and a loaf of bread as an offering. Receiving the gifts, Benedict perceived through divine insight that the glass contained not only wine but also a significant danger.

St. Benedict turned to the servant and said, “Take care how thou carriest this flask, and see thou dash it not against anything, for it is not whole but cracked, and therefore will not hold the wine.” The servant, amazed at these words, carefully wrapped the flask in his mantle and started his journey home.

On his way, he stumbled and fell, and the flask struck against a stone, shattering it completely and spilling all the wine. The servant was shocked, recalling St. Benedict’s words, and he marveled at the saint’s spiritual insight and prophetic capabilities. He collected the fragments of the flask, returned to his master, and recounted what had transpired.

Meanwhile, the loaf of bread that had also been given as an offering was placed by the brethren in a cupboard, but it mysteriously disappeared. When the matter was brought to St. Benedict, he simply said, “The servant who brought it, carried it away again.” And indeed, when they inquired of the servant, they found that this was the truth.

These events further testified to the divine gifts of prophecy and discernment possessed by St. Benedict, who could perceive hidden realities beyond ordinary human understanding. The tale of the Loaf and the Glass reminds us of St. Benedict’s spiritual insight, his foresight into potential dangers, and his ability to discern truth, even when concealed or far removed from him.

The Healing of Servandus

The healing of the Roman patrician Servandus is one of the many miracles associated with Saint Benedict of Nursia.

Ranked just below the emperor and his relatives, the patrician families dominated Rome and its empire. As recorded in Pope Gregory the Great’s Dialogues, Servandus was suffering from a serious illness which the medical treatments of the time could not cure. In desperation, Servandus sent messengers to Saint Benedict, requesting his prayers.

In response, Benedict sent the patrician a small piece of bread which he had blessed. Upon receiving the bread, Servandus, with faith in the saint’s intercession, ate it. Miraculously, his ailment was healed immediately.

Word of this incredible event spread throughout the region, leading many more to seek the prayers and assistance of Saint Benedict, enhancing his reputation as a healer. This episode underscores the profound faith that people had in Saint Benedict and his intercessory power.

The miracle not only enhanced the saint’s reputation as a spiritual figure but also reinforced the belief in divine intervention through the prayers of holy individuals. More importantly, it stands as a testimony to the compassionate nature of Saint Benedict, whose care for the suffering extended beyond the walls of his monastery, reaching out to all those in need, regardless of their status in society.

Vision of a Flaming Light

The Vision of a Flaming Light is one of the most profound spiritual experiences in the life of St. Benedict, illustrating his deep connection to God and his mystical insights into the spiritual realm. This vision, as documented by Pope St. Gregory the Great in his “Dialogues,” is an illuminating testament to St. Benedict’s sanctity and spiritual discernment.

As St. Gregory tells it, one night, St. Benedict was alone in prayer when suddenly, he experienced a divine illumination. It was as if the darkness of the night had been driven away, replaced by a flood of brilliant light. In this overwhelming radiance, he had a mystical vision where he seemed to be transported outside of himself.

In this vision, the entire world was laid before him, gathered together, as he described it, “in a single ray of light.” This wasn’t merely a geographical understanding but a deeply spiritual one – seeing the world bound together in the unity of God’s creation, interconnected through the divine light of God’s presence.

Simultaneously, he beheld the soul of Germanus, the bishop of Capua, being carried to heaven by angels. He immediately sent word to the monastic brethren of the bishop’s passing, which was confirmed a few days later when messengers from Capua arrived to report the news.

This mystical experience of the Flaming Light not only further confirmed St. Benedict’s sanctity but also provided a beautiful imagery of the divine omniscience and omnipresence. It showed that in God, all of creation is intimately connected, and that in His light, there is the illumination of spiritual understanding beyond the boundaries of physical distance and earthly life.

The Future of His Monastery

St. Benedict prophesied that his disciples, at the Monastery of Monte Cassino, would live according to his Rule until the end of the world, and that his monastery would suffer severe tribulation. Indeed, the Monastery of Monte Cassino has experienced destruction and persecution multiple times, but each time it has been rebuilt and the Benedictine Order continues to thrive today.

St. Benedict prophesied that his disciples, at the Monastery of Monte Cassino, would live according to his Rule until the end of the world, and that his monastery would suffer severe tribulation. Indeed, the Monastery of Monte Cassino has experienced destruction and persecution multiple times, but each time it has been rebuilt and the Benedictine Order continues to thrive today.

The prophecy regarding the future of his monastery is a testament to St. Benedict’s gift of foresight and his profound understanding of the spiritual and worldly challenges his community would face. This story is primarily sourced from the Dialogues of St. Gregory the Great.

It is said that one day, St. Benedict was in deep contemplation when he was granted a divine vision. In it, he foresaw the future destruction of his monastery at Monte Cassino. He saw that the monks would be dispersed, the buildings leveled, and all the hard work of the community undone. This devastation would be wrought by the hands of wicked men.

Despite the sorrow this vision must have caused him, St. Benedict did not hide this prophecy from his community. He shared it with the monks so they would be spiritually prepared for the trials to come. In this, we see St. Benedict’s belief in the importance of resilience and faith in the face of adversity.

True to the saint’s prophecy, the monastery of Monte Cassino was destroyed multiple times over the centuries. It was first sacked by the Lombards around 581 AD, nearly a century after St. Benedict’s death, then by the Saracens in 884 AD, and finally, the monastery was bombed during World War II in February 1944.

Each time, just as St. Benedict had foreseen, the monks were scattered, the buildings were ruined, but they always returned. They rebuilt the monastery and continued their work, carrying on the spiritual legacy of their founder. Today, Monte Cassino stands rebuilt and active, an enduring symbol of the Benedictine motto: “Succisa Virescit” – “When cut down, it grows back stronger.” This was exactly as St. Benedict had prophesied – a testament to his foresight and the enduring spirit of the Benedictine community.

St. Benedict’s Holy Death

St. Benedict passed away around 547 AD. His death is shrouded in a sacred aura, depicted in the second book of the “Dialogues” by Pope St. Gregory the Great, the primary source for information about the life of St. Benedict.

According to St. Gregory, St. Benedict foresaw his own death. He informed his disciples of his impending departure six days in advance and asked them to dig a grave. During those days, he gave his final instructions and farewells.

In the last moments of his life, St. Benedict asked to be brought to the chapel. Supported by his monks, he received the Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist and then raised his hands in prayer while standing. As he uttered his last prayer, he died, standing in the chapel, supported in the arms of his disciples. This occurred on March 21, 547 AD, and he was buried next to his sister, St. Scholastica, at the Abbey of Monte Cassino.

The manner of St. Benedict’s death – in prayer, after receiving the Eucharist – reflects his life’s work of seeking God through monasticism. His final act was a testament to the monastic ideals he promoted: prayer, work, and community life.

St. Benedict’s death is remembered in the Benedictine world with solemnity and reverence, acknowledging the significant impact of his monastic Rule, which continues to guide monastic life even today.

The Benedictine Spirit

St. Benedict’s legacy, both in the shape of Western monasticism and in the spiritual insights he bequeathed, continues to resonate powerfully with Catholics worldwide. As St. Benedict himself once wrote, “Listen carefully, my son, to the master’s instructions, and attend to them with the ear of your heart.”

May we all strive to listen more deeply and love more fully, in the spirit of this great saint.

New Book: St. Benedict: Monk, Mystic, Exorcist

Pre-order: Ships by July 25, 2023

Follow one of Catholicism’s most revered saints on his extraordinary journey from solitude to sainthood in a story filled with earthly trials, diabolical attacks, and heavenly triumphs. St. Benedict: Monk, Mystic, Exorcist explores this riveting true story about radical faith and spiritual warfare in the ashes of the Roman Empire.

Benedict of Nursia gave up a privileged life of Roman nobility and an education in Literature and Law for a life of silent meditation in a remote cave. After three years of wrestling with unseen forces and relying on the good will of strangers for sustenance, this cave-dwelling hermit emerged as a spiritual leader.

Gaining noteriety as a humble man of miracles, visions, exorcisms, and prophecies, Benedict’s one-man monastic movement grew to include a legion of devoted followers who practiced his Rule and helped him revolutionize monasteries around the world.

Saint Benedict: Monk, Mystic, Exorcist weaves together remarkable threads of monasticism, mystical experiences, prayer, and spiritual combat to paint a vivid portrait of an enigmatic man whose legacy continues to inspire the modern-day world. 190 Pages. Paperback.

ORDER

St. Benedict Medals, Holy Cards, Bracelets and more

SHOP NOW

SHOP NOW

SHOP NOW